Photography: Jeffrey Hornstein

The man is a tall drink of clear water. Lithe and long, all in white, as is his wont, he floats into his studio, exactly on time. His flowing ideas are waiting impatiently for my camera man to get set up; like flowing liquid swirling through glass – I am concerned they will overflow, and I will not catch them! He looks at me expectantly; what will I bring out of him this bright, sunny day?

Karim Rashid is easily one of the most prolific industrial designers on the planet, with an astounding 4,000 designs in his portfolio. Moreover, his work spans a vast range, from housewares, lighting, furniture and eyewear to hotels, houses, stores and spas. He created the Bobble bottle in 2010. In 1996, he created the Garbo waste basket, now used ubiquitously.

Born in Egypt and raised in Toronto, he graduated from Carleton University in 1982 with a bachelor of industrial design before launching a career that has made him globally famous and sought after by some of the most recognizable brands in the world.

On this warm spring morning, we have met at his studio in New York, the city he has adopted as his home.

For all his dark hair and dark tattoos, still he radiates light. He’s so long and lean that he seems to have to fold down to speak to me on the sinuous grey sofas. He likes to sit close during interviews, partly because he is so soft-spoken. I am worried the microphone will not pick up his quiet voice. Once his thoughts start coming, they flow like a waterfall, and eye contact is essential to ensure that I am following his train of thought.

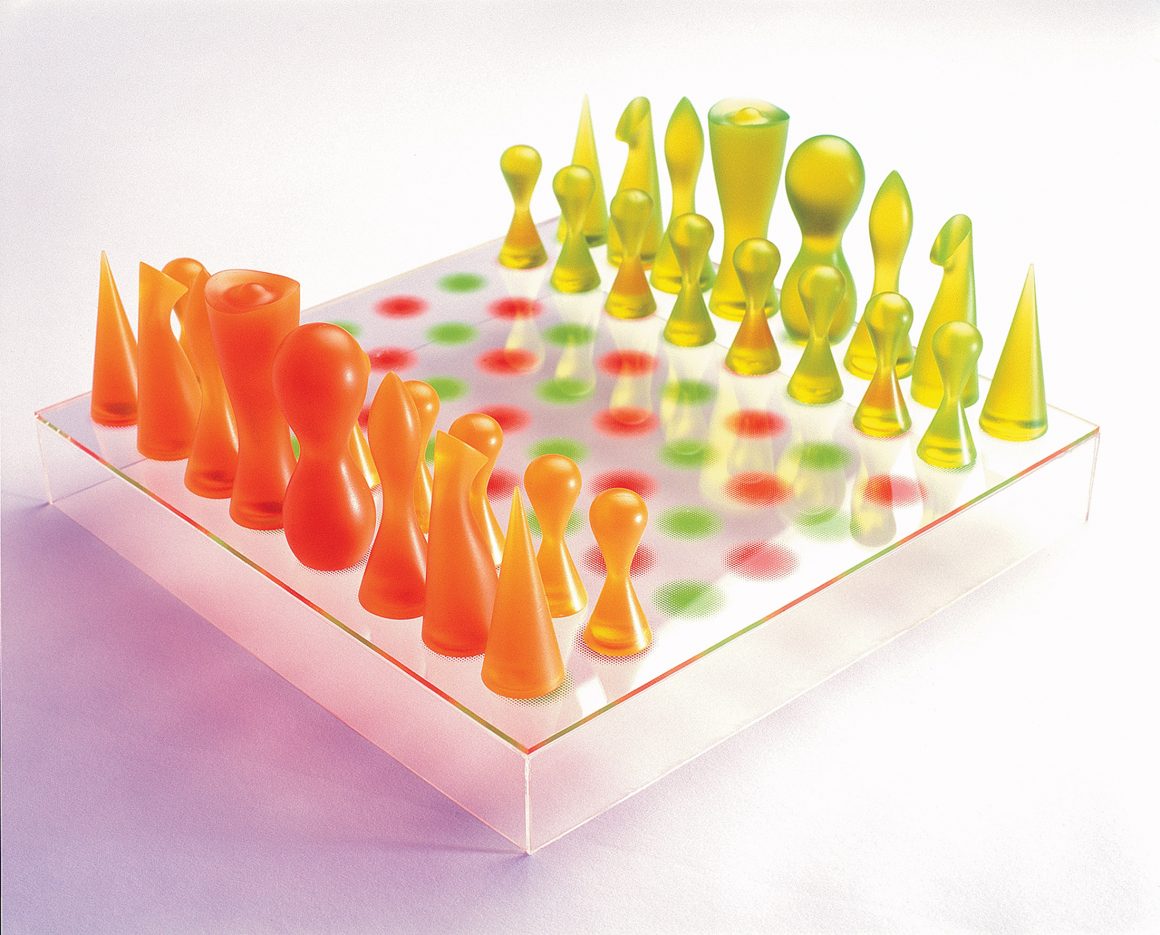

Karim’s studio is a reflection not just of his principles as an artist but of the man himself. Everywhere you look, there is something to learn about him. Many of the products he’s designed over the past 30 years are on display here: the iconic OH Chair, those curvaceous bottles that hold Method cleansers, the Artemide Cadmo lamp. But the space cannot possibly represent the vast scope of his work, some of which is in permanent collections and museums around the world.

The building in which Karim’s firm is headquartered was redesigned in 2013. The front room, where we sit, is flooded with light from a two-storey skylight. It allows natural light into the front reception area, into Karim’s personal office, which is set back on a second-floor mezzanine, and into a glassed-in conference room behind us.

“Space has a huge effect on how you feel,” Karim says, “I used to hate to come to work, doing 12 to 14 hours of my sketching; all of my real design was done at my home. Now I love to come to my studio!”

We discuss his fascination with colour, his love of white and pink particularly, and how not just colours, but stones and materials have energies that affect our bodies and the space around us. Pink, for example, in both natural stones and colours, has protective, healing, and joyful properties. “All life is energies, all light and colour,” he says “Anything that’s not inert is aging, changing with time. Everything exerts an energy. We have to influence this.”

The middle room is an open bank of computers. Designers sit together in a large space, on the east side of which is a long, open window. After our interview, Karim immediately goes and sits amongst them and starts working on a myriad of designs and projects. At the moment, he says, he is working on the design of hotels all over Europe – Germany, Austria and Italy – along with a second resort for Temptation in Punta Cana and a hotel renovation in Greece. He’s also designing a six-star hotel in Bahrain, a hotel in Jaffa, Israel, offices and a youth hostel in Budapest, offices in India, and condominiums in Texas, Washington D.C., and Moscow.

Other projects include a raft of products for companies around the globe: beds, baths and sinks, glassware, a pet collection, a seating system, lighting, new outdoor furniture, tiles, carpets, and packaging for such products as toothpaste, food and kitchen items.

In the last room, almost a warehouse behind the designers’ workshop, full of chairs and tables and the “product archive,” there is still plenty of natural light. The archive area has windows that face east onto the adjoining condo courtyard.

It is here that I found my favourite chair, and when I ask Karim about his most romantic design, imagine my delight to learn that it was this same design: the pink Veuve Clicquot loveseat, he tells me. “I was asked to design a loveseat where the lovers would have to be seated in an old-fashioned way, drinking, facing each other, but opposite, seeing each other, unable to touch,” he says. “And in the middle of these very pink, tall two chairs, is a bright gold plastic bottle to chill the champagne, a very romantic idea. I had fun designing this chair.”

In the debate about form, function and beauty, he says he cannot understand the “conceit of beauty for its own sake.”

“A thing must be functional,” he says. “A chair must be comfortable. Function must conform to form; form must conform to function.”

While he’s enamoured of sugar-based polymers as a substitute for the toxic plastics currently used in products, he concedes that the higher cost of these polymers is similar to the premium paid for organic foods. Consumers don’t want to pay more for them.

How can we create a safer, greener Earth by producing products with sugar-based polymers if consumers refuse to pay for them? “It’s coming,” he says. “They will. We have to be the influencers who create the products that eventually become so ubiquitous that the days of waste are gone.”

Like all great artists and thinkers, he has invented his own lexicon. Brilliant and well-educated, he has converted the words “art history” to “style.”

Toward the end of our interview, I challenge Karim on some of his ideas. He says we are now in an era of “democratic art. We are all now bioneers.”

I argue. “Not everyone is born to be a designer like you,” I say. He counters: “Yes, everyone is born creative; all are born with design in their souls. It is just that at some point, it is beaten out of them!”

“Nevertheless,” I say, “you can’t expect every adult to be capable of designing their world as you do.”

He is undeterred. “All children are creative; it is innate in us,” he insists. “But for most people, once they cannot be creative as artists, the procreative act becomes their creative act. Courting is a creative act!

We are here only to create. Our intellectual or physical creation keeps our existence alive!”

I love the optimism of this man. I love that he has such faith in the human spirit. And, guru that he is, we leave it at that.

He loves to talk about destiny, about work being one’s destiny. I agree. I say: “We are indeed lucky when the work we choose to do is our love.”

He says (again) that everyone has a destiny, and that he is lucky that he knows that his has always been to be a designer, that he knew it from the age of six because his father, Mahmoud Rashid, a set-and-costume designer, gave him pencils and allowed him on his sets.

For this series of articles in which I am interviewing extraordinary Canadian designers, architects, painters, builders, I will be asking each one of them the same overarching questions: “Why do you do what you do? What spurs you on and what do you have left to achieve?” In this interview with Karim Rashid, we found, as with Chaki, that there is the drive to create, the optimism of belief in one’s destiny, and the need, no matter how much one has achieved before, to continue the creative process.

I am not sure that all people are so singularly lucky to know their destiny and to follow it. But I am sure that we are lucky that Karim Rashid has found his, and that he is following it. And I know that we will all enjoy whatever he has to show us next! •

Karim Rashid

www.karimrashid.com

202-929-8657