It’s a ubiquitous, popular line of pottery found in many homes. Yet how many of us know the story behind Blue Willow?

The body of a Blue Willow piece depicts a pagoda with a pavilion or teahouse on the right, an apple tree behind. A willow tree overhangs a bridge over which three figures are crossing. A boat floats in front of a small island while two doves fly overhead.

Despite its modest dimensions, the piece holds an astonishing amount of visual imagery and information.

The origin of Blue Willow begins with a Chinese legend: Li-Chi lived in a pagoda beneath an apple tree. He had a beautiful daughter named Koong-Shee who was to marry an elderly merchant named Ta-Jin. However, she fell in love with Chang, her father’s secretary, who was fired when it was discovered that they were meeting secretly. Koong-Shee and Chang eloped with the help of her father’s gardener. On the plate, they are seen running across the bridge with the angry father in pursuit, a whip in his hand. The lovers use the boat to escape to Chang’s house. The furious father discovers their retreat and pursues them. The lovers are about to be beaten to death when the gods take pity on them by turning them into a pair of doves, depicted at the top of the image.

There are variations of the design, taken from Chinese wares (note the English spoon rest, a direct copy with the pseudo-Chinese mark), and there are various versions of the tale. In one, Chang runs carrying a box of jewels given to Koong-Shee by Ta-Jin, the unwanted betrothed.

The current form of Blue Willow originated in England in 1780 from a design by engraver Thomas Minton. He sold the design to potter Thomas Turner, who mass-produced it on earthenware.

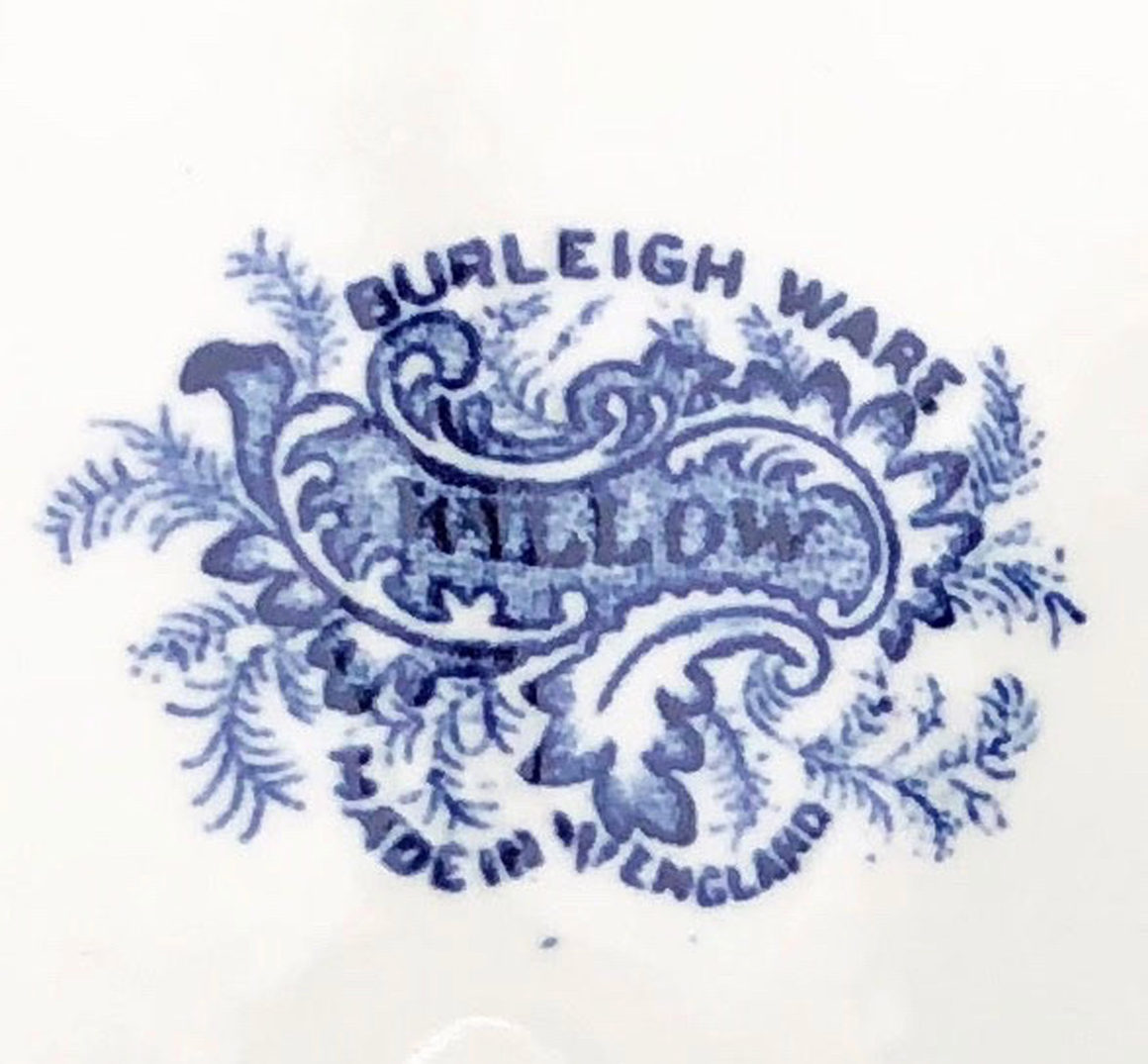

Other English factories copied the pattern. Early versions (1830–1860) are either unmarked on the underside or bear small blue symbols that do not help owners identify the provenance of their pieces. In the absence of copyright laws before 1842, designs were pirated by various factories. Later, engraved marks were added to designate the origin, as in the example shown.

The desirability of Staffordshire ware comes from its surface decoration rather than its composition. It was easy to hide potting errors by covering the piece with an overall design. Often, transfer papers were not carefully applied, making join lines or transfers on borders apparent. Transfer-printed designs were used to mass produce dishes quickly and cheaply to meet demand and undercut Chinese imports.

In 1986, my partner Ellen Lyons and I travelled to Stoke-on-Trent, known as the “potteries.” During my guided tour of the Minton factory, I observed every stage of pottery-making. I collected broken pieces and transfer papers, and I took notes to help tell the story when I returned home.

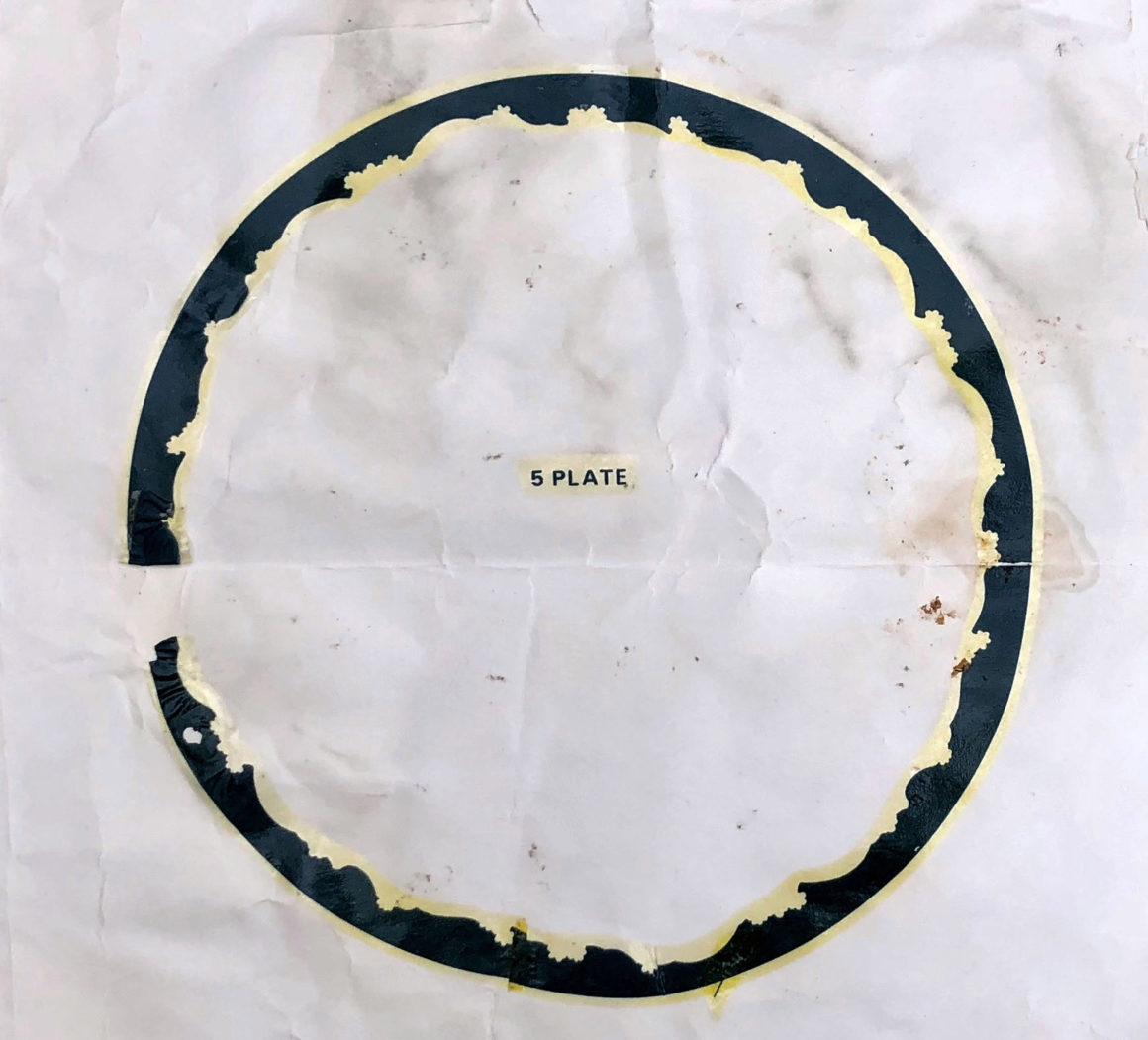

On the Blue Willow plate depicted here, separate transfer tissue papers were used for various surfaces: one for the border, another for the centre image. Imagine a more complex piece such as a soup tureen on which one transfer paper is needed for each side of the body, another for the cover, another for the knob, and others for the handles and borders. See the photo of the tureen (opposite page, top).

Each design was engraved on a copper plate, covered with a black tar-like paint. Tissue paper was applied to the copper plate to absorb the design, then lifted and transferred to the designated place on the piece of pottery. The piece was kiln-fired, setting the design into the plate.

During the 1760s, pictures on copper plates were made of small engraved lines done with a tool called a “graver.” The thickness of the lines was controlled by hand pressure, requiring great skill. A copper plate had a life-span of 600–800 “pulls” or transfers.

The 1800s saw the development of stipple engraving in which images were etched on copper plates, creating tiny dots in graded sizes. The result: pictures with greater depth, contrast, perspective.

By the mid-19th century, celluloid cut-out designs were applied to the ware, creating the decoration method on most of the plates we use today.

Why is blue-and-white so universally beloved?” asks Mary Gilliatt, author of The Blue and White Room. It has been a colour combination for centuries. The Chinese associated blue with immortality while the Egyptians believed it represented virtue, faith and trust. In East Africa, blue is a symbol of fertility and childbirth.

I asked my daughter Gillian if she liked Blue Willow porcelain. “Whenever I see the Willow pattern I look for the two birds,” she said. “The birds are the heart of the story. It’s a story about forbidden love, an angry father and certain death. Yet they (the lovers) persist. And their love conquers everything, even death. It’s a story about hope and redemption. I always smile whenever I see those birds; they represent freedom and the power of love.”

The different shades of blue and their tie to Nature—sky and sea—create an appealing and warm atmosphere that transcends traditional and modern tastes. Although we are in a period of neutral greys and beiges, don’t underestimate the power of blue and white to return to our contemporary living rooms some time soon. •

Originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue.

Lana Harper

www.lyonsharperantiques.com