One of the things that never changes is the desire to meet over a cup of tea. The drinking of tea is such a pervasive custom in England, for instance, that we sometimes forget it originated in Asia.

Tea was expensive when it first made its way from China to Europe. Although the Chinese had been imbibing it for a couple of millennia, it wasn’t until the 18th century that it was embraced by Europeans. Its cost ensured that only the wealthy could afford it.

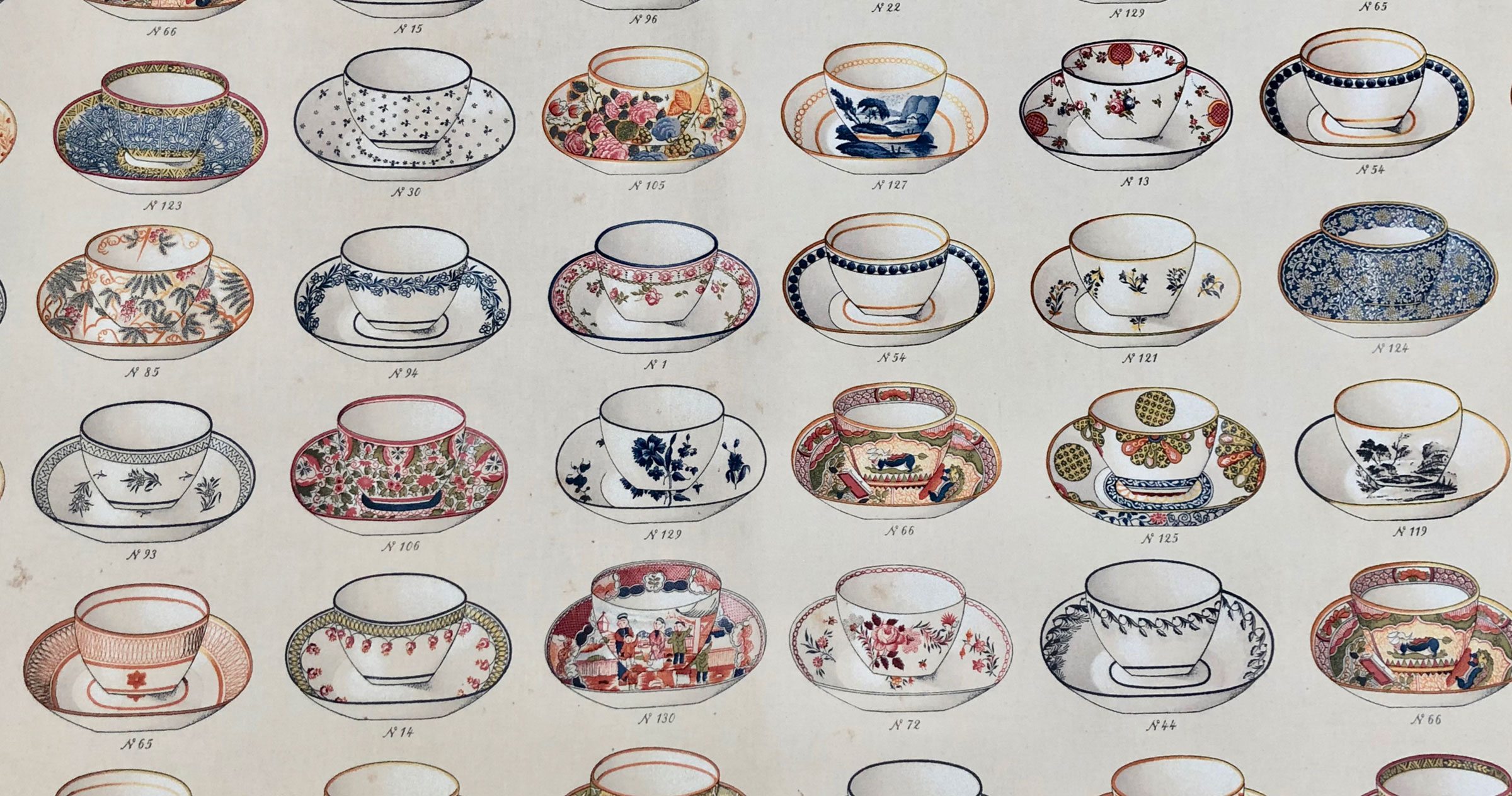

Concurrent with the growing fashion of tea-drinking at that time, the production of porcelain—which furnished teaware—was evolving into an industry in England and Europe during the 1770s.

The early porcelain was delicate and translucent. Hold a piece up to the light and you can see right through it. My daughter, Gillian, believes that part of the appeal of the teacup is that while it appears to be delicate, it’s strong. In fact, if you turn a teacup upside down on a carpet, its bell shape will withstand a person’s weight. This was a selling point when my son, Russell, worked for Royal Doulton.

Drinking tea has long been a social custom at gatherings of such groups as embroidery clubs, church assemblies, and family get-togethers. Any reason to congregate merited a cup of tea. And damp, cold weather in the absence of central heating enhanced its appeal.

Rather than today’s traditional cup and saucer, early 19th century tea sets included 12 trios; each trio consisted of a tea cup, a coffee can and a saucer.

Teacups

Early teacups—copied from Chinese prototypes—were small, and they lacked handles. The most famous ones, made at the Meissen factory by Böttger, and decorated by Johann Gregorius Höroldt, date to the 1720s. One such cup was up for auction in Vienna last July for between €7,000 and €10,000.

Handleless cups were difficult to hold when hot, so an accompanying saucer was developed to be raised to the lips.

As handles were developed, they evolved in shape as teacups were made larger. Usually unmarked, the handle’s shape was a way of determining a cup’s factory of origin.

The Minton teacup, inspired by designs in old Minton pattern books, became a favourite. During an antiques-buying trip in England, I found a salesperson who sold me the display Minton teacup fabric in a shop window that I was desperate to have.

Teapots

Globular shape c1800, larger oval shape c1825

Tea boxes, wood and tole

Teapots are another essential element in a tea service. They were often copies of early silver-teapot shapes.

Teapots made between 1775 and 1800—copied from Chinese models—were globular, barrel-shaped and small. Because tea was a luxury, it was kept in caddies and tea boxes for safe storage. Tea boxes were crafted of wood, tole, and even rolled paper. There were small single ones and large double ones, fitted with separate containers for black tea and its green counterpart.

By 1810, the drink had become more affordable, resulting in the production of larger teapots. Some had steam holes in their lids. Others, called turreted pots, had a single hole in the centre of a turret-shaped knob (see photo, right).

In the Victorian era, teapots were raised on feet to prevent them from leaving marks on tables. Earlier teapots often had matching stands that complemented the pots in shape and decoration.

Some teapots were decorated with hand-painted names, dates, mottoes, and verses. In some collections, the pot is the only piece marked with the name of the factory where it was produced; the name and mark might be under the lid. Many an hour has been spent by experts consulting books and examining patterns and shapes to determine what factory produced a piece.

Milk and Sugar

The development of vessels for milk and sugar followed. Popular in the 1800s were small sparrow-beaked jugs that had pointed spouts. There was also the helmet shape (turn the jug upside down and it looks like a helmet) copied from Chinese versions.

Sugar bowls, sugar pots and sugar boxes were other components in tea sets. Some were covered, others were not, but their shape was similar to that of the teapot.

Slop or waste bowls were also standard items. They were used to pour out the dregs of tea leaves from teacups before refilling.

Spoon trays held six teaspoons. They tend to pre-date 1800. After that time, a teaspoon could be placed on a saucer, designed with an indentation for the cup and a wider rim for the spoon.

Teaware as Gifts and Displays

A lovely use for a tea service is display. I have three sets on mahogany shelves in my dining room: Spode, Ridgway and Coalport. Each exemplifies the history of porcelain-making in the early 19th century.

Teaware is given to commemorate special occasions. In my case, Ellen Lyons gifted me an English New Hall cup and saucer (circa 1810), decorated with flowers. It was accompanied by a note asking me to be her partner in the antiques business.

I also have a fond memory of my 50th birthday celebration: high tea at the Ritz Carlton. The maitre d’ allowed me to bring in teapots as centrepieces for the tables.

Taking tea continues to be a ritual all around the world. I am reminded of the words of William Gladstone, one of England’s longest-serving prime ministers during the 19th century, who wrote:

If you are cold, tea will warm you;

If you are too heated, it will cool you;

If you are depressed, it will cheer you;

If you are exhausted, it will calm you. •

Lana Harper, who holds a bachelor of arts from McGill University and a masters in translation from l’Université de Montréal, is a member of the Canadian Professional Appraisers. For 30 years, she partnered with London-based Ellen Lyons in buying, selling and exhibiting porcelain at fairs in Canada and the United States. Currently, she does estate, private and online sales and appraisals. (www.lyonsharperantiques.com)

Originally published in the Winter 2020 issue.