Tourists now flock to London, England to catch a glimpse of Big Ben, the Tower, Buckingham Palace, or other must-see landmarks. But in the late 17th century, the skyline itself was the attraction.

The great painter Canaletto immortalized the cityscape, seen from afar, in oil paints. And Peter the Great was so taken with what he saw in 1698 that he decreed the new Russian city of St. Petersburg should emulate it.

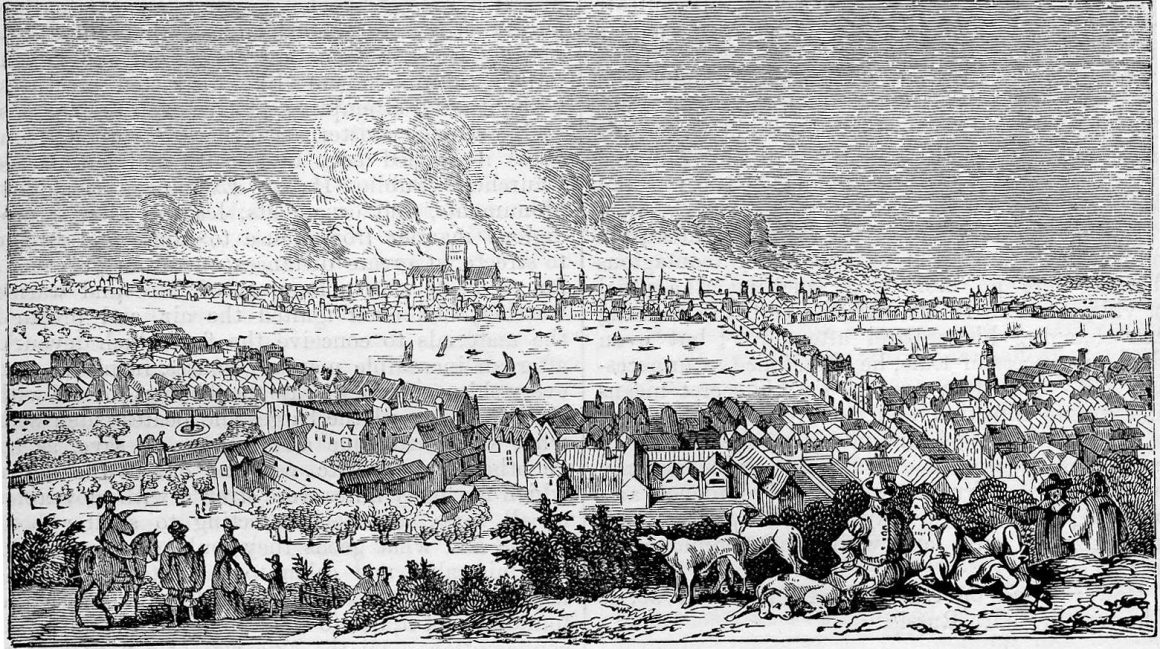

London’s then incomparable beauty — which would last until future centuries punctuated it with jutting skyscrapers — was all due to a fire. For it rose like a glorious phoenix from the ashes of the Great Fire of London that began in the early hours of September 2, 1666 and raged for four days.

What burned: A warren of houses made of wood (even the water pipes were made of it) and thatch over a mile-and-a-half area along the River Thames. The homes were built cheek-by-jowl, with upper floors “jettied” – or cantilevered out over the streets. They were so closely placed that they almost touched neighbouring properties. Some examples of this architecture remain, such as Holborn’s Staple Inn (1588).

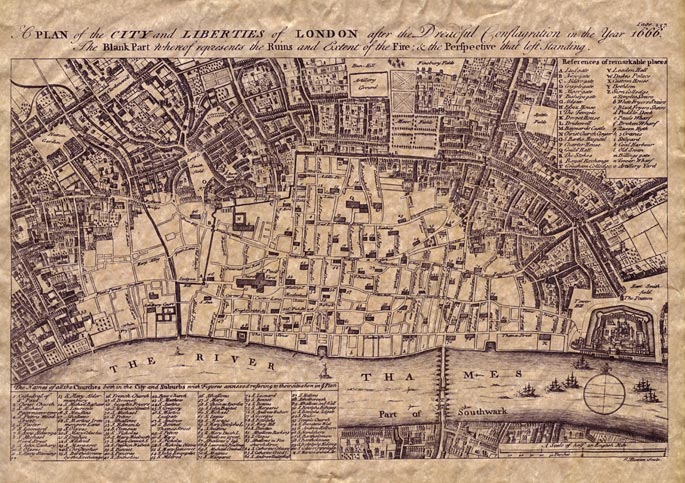

The fire’s aftermath saw many of the city’s buildings and 87 churches, including St Paul’s Cathedral, destroyed. One-fifth of its inhabitants, some 80,000 people, were homeless. Surprisingly, fewer than a dozen people died, though some historians question the statistics.

A frantic bout of urban planning ensued. First, King Charles II issued a royal proclamation that halted any construction until new regulations could be put in place. When passed, the London Building Act of 1667 provided comprehensive measures aimed at reducing fire risk.

The Act strictly forbade building with materials other than brick or stone, and specified that they should be flat-fronted. Everything from types of windows and shop signs to wall thickness was laid out. And for the first time, inspectors were not only hired but given the authority to enforce them. Penalties included having a non-conformance house torn down.

Five prominent architects of the day submitted plans to rebuild the City of London. The most grandiose was from the era’s most famous, Sir Christopher Wren. His drawings showed broad avenues emanating from a central memorial to the fire victims. John Evelyn proposed widening the streets and implanting squares by the river. Robert Hooke’s plan was more linear. In the end, none was implemented. Because the royal coffers were so slow to open, private initiative took over. Wren would, however, go on to design the iconic St. Paul’s cathedral, which replaced the one that had burned.

Commentators such as Ike Ljeh, architectural correspondent for UK-based Building, speculate that the building restrictions plus the frenzy to rebuild led to the emergence of the English Baroque style. “This age still represents one of the most fruitful, productive and dynamic periods in the entire history of British art and architecture,” he writes. •