PHOTOGRAPHY: JEAN BLAIS

Wry humour. A romantic and penetrating mind. An indomitable spirit.

He experienced humble beginnings, the ups and downs of being a creative soul, being an artist in an uncertain world, a child during the Holocaust who was hidden by righteous gentiles. Could this be where his optimism came from? He moved during childhood to Israel (before it was Israel), then Paris as a young man. Could this be where his romantic soul came from? Then to the New World and started a family here. Could this be how he developed his determination?

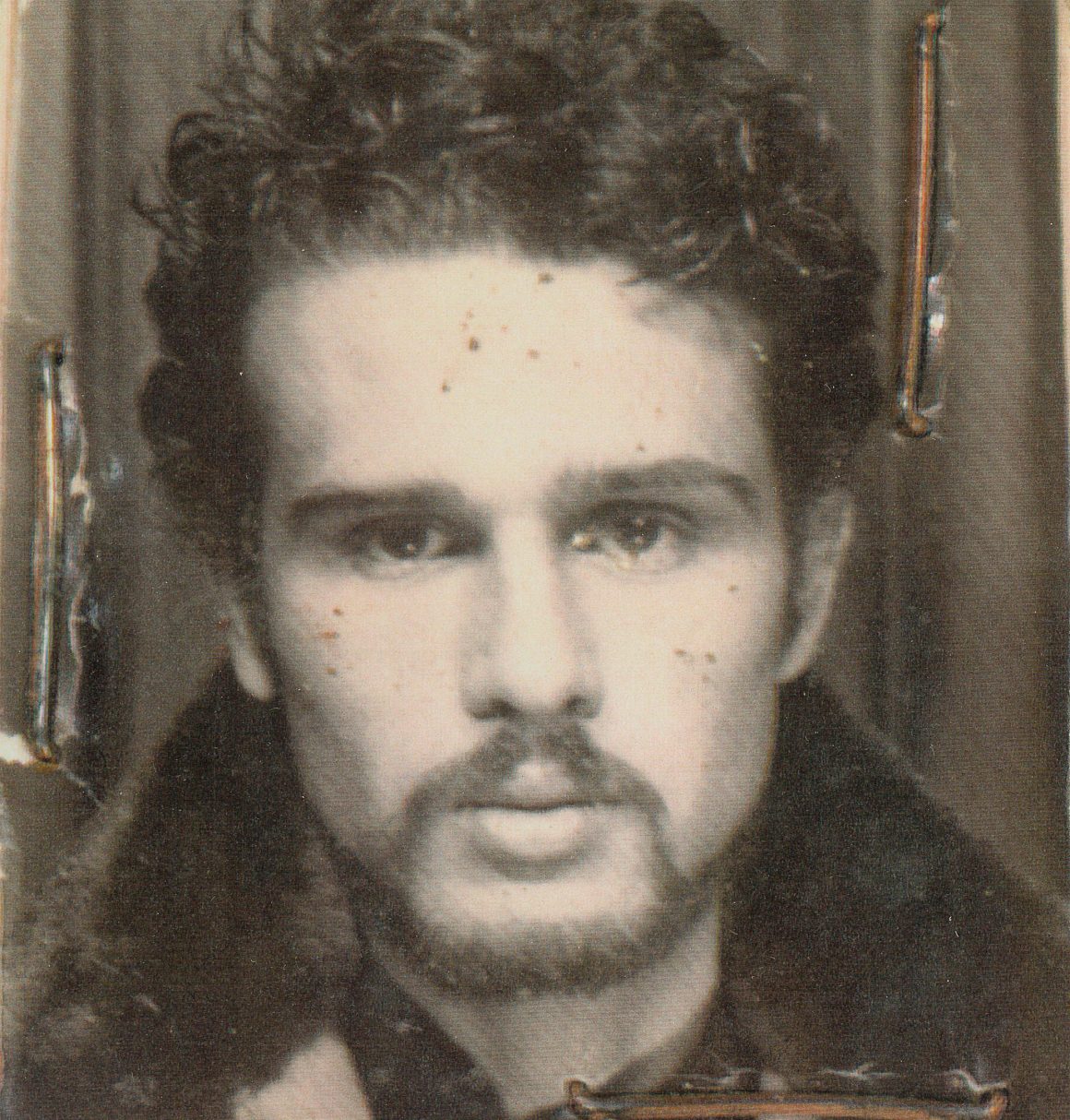

And now, battling Parkinson’s disease, artist Yehouda Leon Chaki is still, at the age of 80, producing some of the most fabulous art of his 70-year-long career.

Chaki, as he is simply known, was born in Athens, Greece on December 11, 1938 to Sephardic Jewish parents Flora and Benzion Sciaky. He and his family spent five years being hidden by Christians during the Second World War, and relocated to the city of Holon in pre-Israel Palestine, when the Sephardim were considered second-class citizens.

Chaki simplified the spelling of his surname and uses it as his only name. All his life, he says, people have referred to him just as “Chaki,” including his adoring wife. When I ask him why, he tells me a story about what his name means. His father explained that the three letters of his name are: שׁ = Shem (name) ק = Kadosh (Holy) and י = Israel. Thus, the name means that “we should be a holy name or light for our nation.”

Chaki’s loyal studio assistant, Hannah Sophia Aronoff-Stachtchenko, says the artist often declares: “It’s a war out there.” Knowing that he goes to work in his studio every day led me to wonder: Is the studio his refuge or his own private battle ground? Are his canvases the places on which he can find shelter from the world or where he makes his peace with the wars he has fought with the world outside?

“What’s the war?” I ask him.

“There’s always a war somewhere,” he says. “I’ve been through so many: in ’41, I was hiding. In ‘48, ’56 … Everyone is still trying to find their place. Now, I have a fantastic painting to show you – the flowers are fighting each other for space on my canvas. It’s fantastic!”

In Israel, his family was so poor, there was no money for art supplies. Chaki had only six crayons, but his need to express himself was so irrepressible that he used every resource available. He drew a view of his neighbourhood with shoe polish on a wall in his home. One day, Dr. Itzhak Scheinin, the family physician, making a house call to Chaki’s brother, noticed the sketch on the wall and asked who had done it. Learning that it was 10-year-old Chaki, he decided to take him and his drawings to a friend, Ludwig Schwerin, a famous artist, who recognized the youngster’s talent. And so, Dr. Scheinin, with no children of his own, became young Chaki’s patron. This relationship would become one of the most important influences of Chaki’s life, and would last for the rest of Scheinin’s life.

The doctor sponsored Chaki’s education at the Schwartzman Arts School for 11 years, then the Avni Academy of Arts in Israel, from which Chaki would be accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts.

“I paint ideas. You, as the spectator – you complete the ideas.” Chaki in his studio, Winter 2018

As a young man, Chaki had such acute vision and superb spatial sense that when he was called up for military service in Israel, he would climb up hills during the night and return to draw for the army what he had seen. From this experience, he explains, he learned techniques that he would use in his own art later. “My landscapes are not just landscapes,” he says. “There are never any roads; there is no perspective. There are no telephone poles, no human elements. That is why they are so restful. Faces are not restful; faces are not kind; faces do all bad things in the world.”

Throughout 1958 and 1959, Chaki saved money to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He did so by creating posters and starting a community newspaper, for which he sold advertising. Some of his logos still exist, including one for Pina Aduma coffee and La Favorita coffee machines.

He saved only $200 for the boat passage and $20 for the student pass that bought one meal a day for a month in Paris, but he had no money for rent.

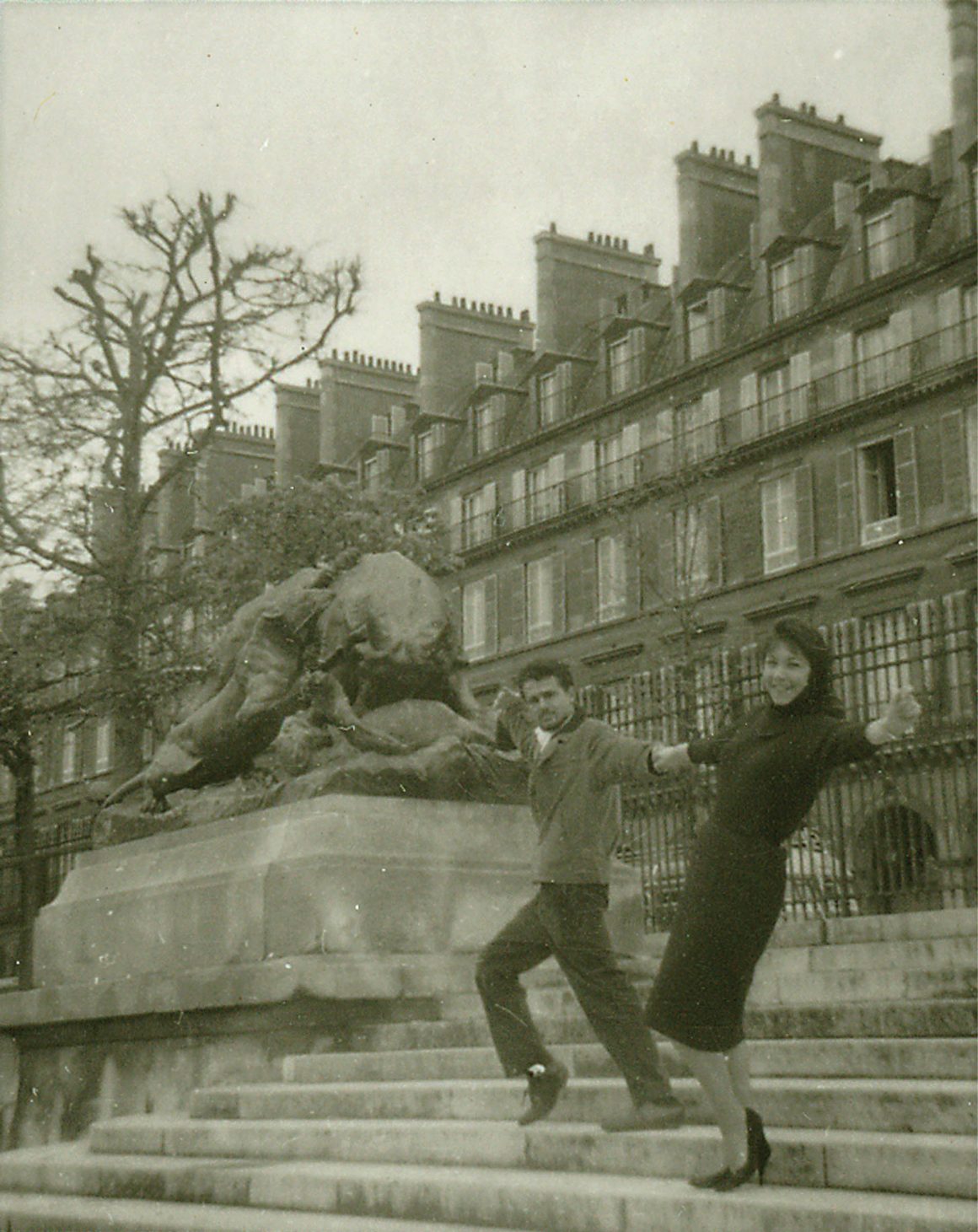

Needless to say, he describes himself, upon arrival, as “very thin and running a fever.” As he sat in the famous Café Select on his third day in the City of Light, with nowhere to live, and no money to even buy a cup of coffee, he befriended Igal Ma’oz, an Israeli painter. Already enjoying a good career, Ma’oz invited Chaki to his home, prepared him a breakfast of an egg and bread, and found him a job carrying 50-kilo bags of cement. They remained friends for life.

Once Chaki regained his health, he took over a sixth-floor maid’s-room apartment from an Israeli student who was leaving Paris. The room was just 10 by 10 feet and it had a slanted ceiling that he would bump his head against; but it had the magnificent light of the Parisian sunsets and enough room for a bed and an easel. The bathroom was two floors down, but Chaki loved it.

He went to the students’ kosher cafeterias where he could eat almost for free, and it was there that he met Grace Aronoff, who would become his wife. Theirs was a magical, whirlwind courtship that has resulted in two children, grandchildren, and love and respect lasting 57 years.

Chaki cites his time in Paris as the most important formative chapter in the development of his art. He walked through the Louvre every day en route to his apartment across from the Opéra Comique. He reveled in days spent drinking up the greatest of painters, and nights spent in the company of the best singers and artists of his time. He adored, among others, Chaim Soutine, Jacob Epstein, Modigliani, and Yves Klein, whose famous cobalt-blue left a lasting effect on him. “These artists, I was influenced by their aura. They gave me a chance to see that one day, I am going to make a living making art,” he says during a recent interview in his Montreal studio.

“If I paint a face, I invent it, We are living in a beautiful time. I don’t copy a face.” Chaki, March 2019

Sitting in the Café Select, across from La Coupole, he’d watch Marc Chagall and Mané Katz walk by. Occasionally, he says, one of them would wave and buy him a coffee, because he had done one of them a favour. He can’t remember what he did; perhaps it was drawing or copying for them; but he remembers that he met Mané Katz at Yaacov Agam’s house, where the artist was storing his paintings. Just being around these great artists, watching them, was the best education a young artist could dream of.

Chaki is renowned not only for his large, colourful still lifes, full of energy and generous use of impasto, but also his many installations throughout the years across Canada. He’s widely recognized as one of this country’s most important painters.

I am proud to know him (we met when I sang as the cantor at his daughter’s wedding some 17 years ago) not just because I admire his art, not because he sings love songs and dances the tango, which helps him move with his Parkinson’s, but because his indomitable spirit and irrepressible good humour are an example for us all, of how to live the best life we can. A life full of fire.

Because we all know somehow that there are many wars raging out there, and it is good to be able to look to Chaki and his art as an example of how to win them. ●

In honour of Chaki’s 80th birthday, the following art galleries will host presentations of the artist’s work.

Odon Wagner Galler ~ 198 Davenport Rd, Toronto, Ontario 416-962-0438 ~ http://www.odonwagnergallery.com

Galerie de Bellefeuille ~ 1366 Avenue Greene, Westmount, Quebec 514-933-4406 ~ www.debellefeuille.com