Photography: Drew Hadley

On a hot, cloudless summer’s day, Sacha Pommepuy hops off his bicycle, doffs his helmet, and sits down at an outdoor piano to play.

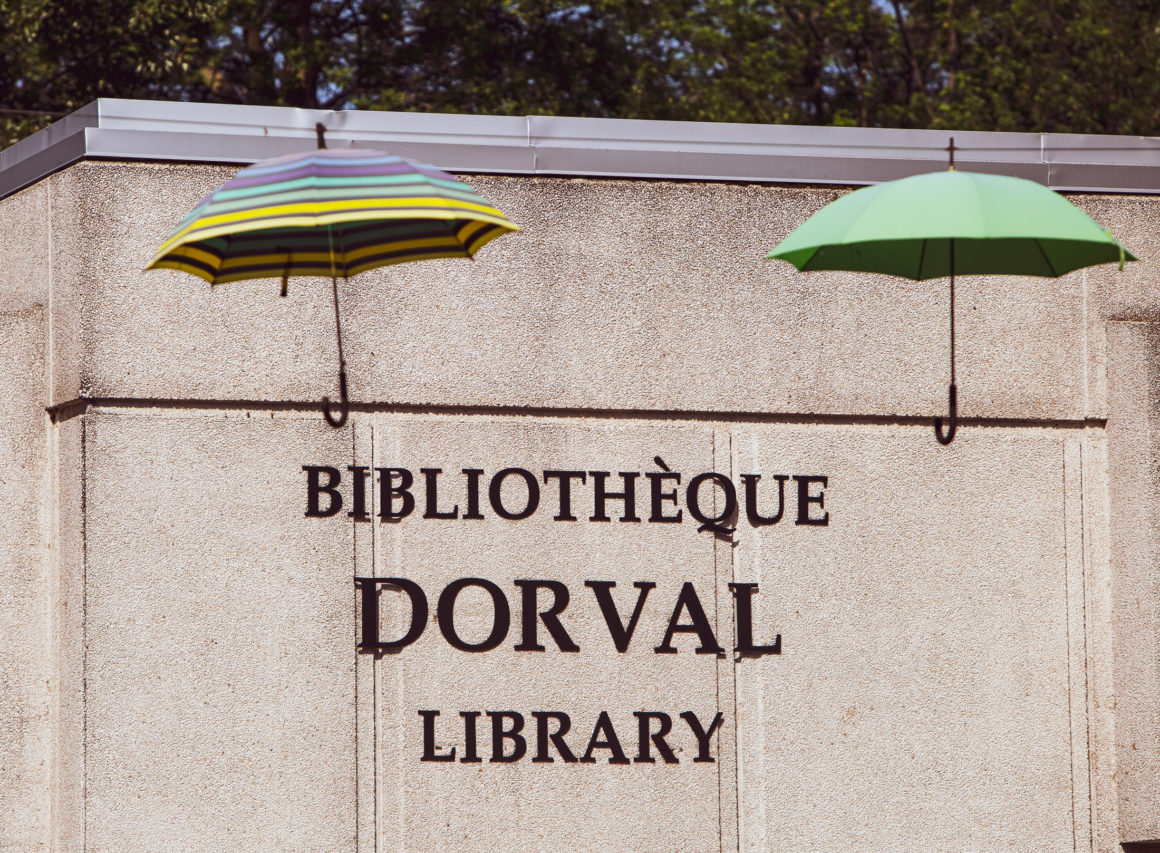

This particular piano, outside Dorval’s municipal library, is one of approximately 50 such uprights positioned in public spaces around the greater Montreal region. Stationed outdoors during the summer months, they’re there for any passerby who wants to stop and tickle the ivories.

“I’m an avid cyclist and I combine my love of cycling with my love of music,” says Sacha. “So, I ride around and play pianos. I start in Dorval, move on to Verdun. I play in St. Lambert, the Atwater Market, Concordia University, Sherbrooke and McGill College, Mont Royal Boulevard, Laurier Street. I know all of these pianos.”

But Sacha’s musical peregrinations are only part of the astonishing story of this remarkable man. What people don’t know when they stop to listen to him play is that he composed all of the pieces he plays. He uses no sheet music, playing strictly by ear, and he has had no formal musical training.

Those who hear his performances are entranced. Some of the music has a boogie-woogie beat; some of it sounds almost classical; some is just plain soothing. He has an impeccable sense of rhythm and pacing. “Sometimes, I’ll start to play a piece and I wonder where I’m going with it…how I am going to end it. It can go in any direction,” he says.

The music pours out of the piano despite the fact that Sacha has severe hearing loss, reduced by about 60 per cent over time because of a congenital condition called Usher syndrome. “My parents discovered it when I was four,” he says. “I have two younger brothers and one of them also has it.” For the uninitiated, Usher syndrome, also called Hallgren syndrome, is a rare genetic disorder that results in a combination of hearing loss and visual impairment. There is no cure.

Sacha, 46 years old, says that he has always had music in him. “When I was six, there was a piano in the house,” he recalls. “My dad played it before going to bed. I could hear it and I’d say to myself, ‘You missed a note. You almost got it.’ Sometimes, I’d play on the piano keys. The first riff I played was music from Jesus Christ Superstar. My mother had the record.”

Sacha’s parents enrolled him in piano lessons. “I went to two or three lessons and told my mother I didn’t want to do it anymore. I didn’t want to learn notes. It was easier for me to listen to music and then play it. My brother, Youri, stayed in the lessons and the teacher recorded them for him. I listened to my brother’s lessons and learned.”

He decided in high school to join the school band. “The music teacher wouldn’t allow it because I couldn’t read music,” he says.

After high school, Sacha studied film, animation and sculpting at John Abbott College, took hip hop dance lessons with his brothers, worked as an extra in movies, did some fashion modelling, became a magician.

He had gigs doing magic tricks at birthday parties and corporate events, and made a series of YouTube videos about magic. As small children, he and his brothers had taken tap dancing and ballet classes. “Once we got into hip hop, we performed in all kinds of shows,” Sacha says.

To earn money after college, he did odd jobs: bagged groceries, did outdoor labour for the village of Senneville, delivered pizza. “The problem was my deteriorating night vision,” he says.

It got worse. By 2015, “I had 20 per cent of my eyesight left and suffered from tunnel vision. I lost my driver’s licence and went into a depression. I’d always been so independent.”

He cycled across Canada to raise money for a foundation that finances research to fight blindness. And then he began cycling year-round in Montreal “as therapy for depression.” That’s when he discovered the network of public pianos and began playing to “bring music to people.” The unspoken rule at public pianos is that a pianist must vacate if someone else wants to play. “But no one kicks me off,” Sacha says, laughing.

His musical tastes are eclectic. “Rock and roll from the 1950s resonates with me, and I love Mozart…allegros and adagios.” He continues to play by ear. “I listen to a piece of music and figure out the pattern and phrasing,” he says. “Some pieces, I get in two or three minutes.”

As for his own compositions, he doesn’t know where the music comes from, where it originates. “I hear it in my head,” he says. “I hear it better when I’m not wearing my hearing aid.” He records whatever comes through, so he can play it again. “I’ve composed about 200 pieces. About 25 are performable.”

Sacha wants young people to know that they can overcome challenges to thrive. So, after learning public speaking through Toast-masters, he began addressing groups of high school students about his experience. Youri and Sacha, who share a house in Dorval along with Sacha’s girlfriend, both work in their dad’s medical equipment company.

And the music continues to flow into Sacha’s head. “I believe that everything happens for a reason,” he says. “What are the odds that I would lose my driver’s licence and suddenly discover that there are pianos all over the place? Someone even gave me an 1895 piano in good shape.”

As soon as Montreal’s quarantine is lifted and the pianos are brought out of winter storage, Sacha Pommepuy will play again. Until then, his music can be heard on iTunes and Spotify. He’s looking forward to playing outdoors again. “I do it almost every day during the summer,” he says. “If I’m going to play music, I might as well do it for people to enjoy.” •