Photography: Drew Hadley

At 94, Montreal artist Rita Briansky is still as loving and fearless in her art as she has been in her life. Her paintings are in more than 60 permanent collections across Canada, including the National Gallery, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musée du Québec, and the Winnipeg and Vancouver Art Museums, to name just a few.

This renowned and award-winning Canadian painter was born in the north-eastern Polish shtetl of Grajewo in 1925. Her family immigrated to Canada in 1929 and settled first in Ansonville in northern Ontario, later moving to Val D’or, Quebec, and finally to Montreal when Briansky was 16, in time for her to study with artist Alexander Bercovich at the original YWHA in Montreal.

Briansky remembers the hardships of living through the Great Depression (her family arrived in Canada on October 29, 1929). She recalls learning to create paper flowers with her Ukrainian friends in Ansonville. “I was drawing before I could write; I was always drawing.”

She says that it was the great Yiddish poet, Ida Maze (aka Ida Massey) who helped her find babysitting jobs in Montreal and free second-hand books so that she could complete her high school education at the former Baron Byng High School on St. Urbain Street. She took a job in a lingerie shop to help pay for her tuition.

The family lived on Park Avenue, in a neighbourhood settled by Jewish immigrants from Europe.

About her first real art teacher, Alexander Bercovich, Briansky says: “What made him so important for me, is that he respected me as a serious student. He believed in me. He wasn’t an articulate man; he stuttered. But all I needed was someone to believe in me and he did. He gave me a key to the studio in the old YWHA building on Esplanade St. where he taught art so that I could paint in a quiet place.”

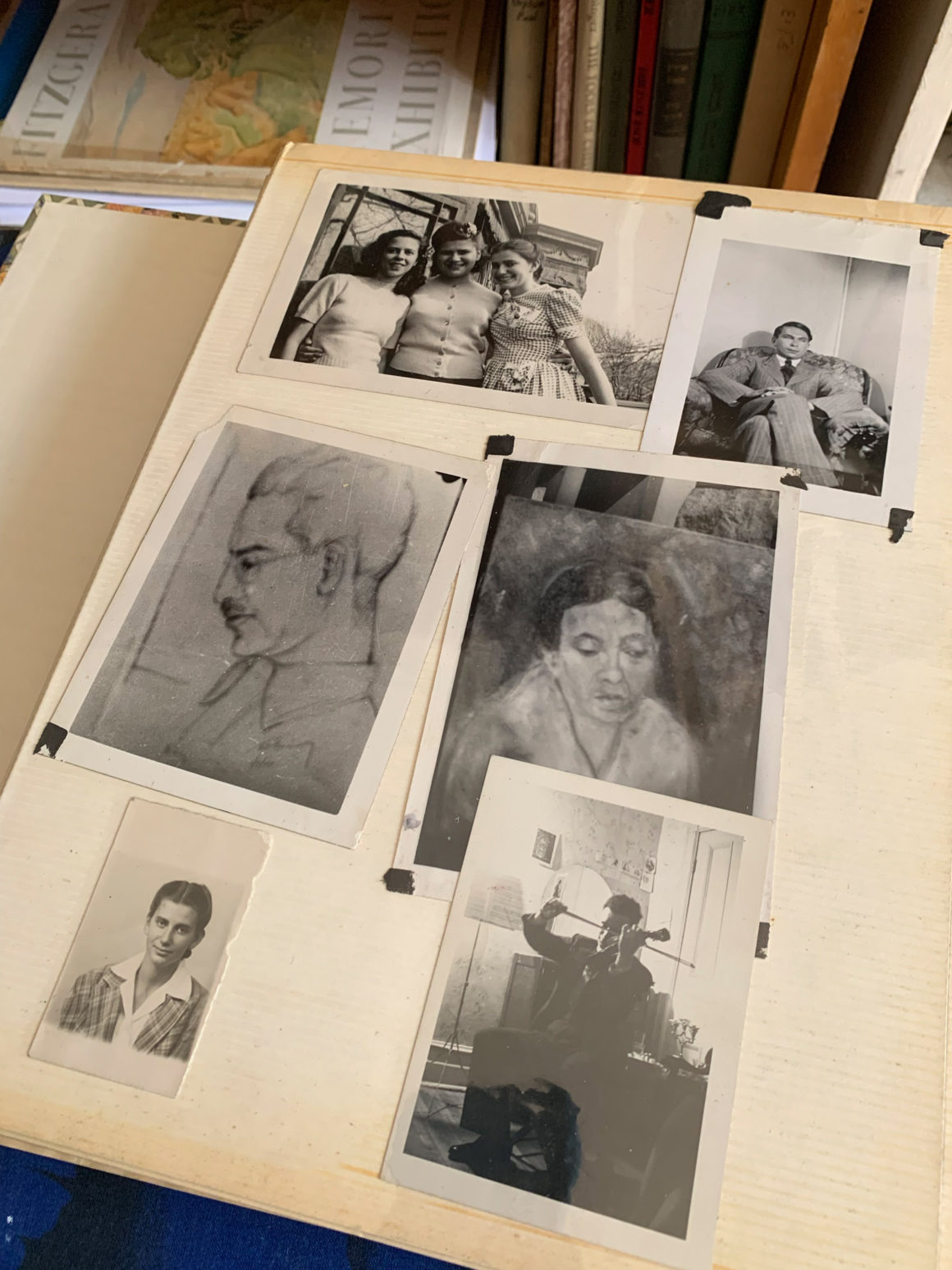

Four years after her 1942 high school graduation, Briansky left Montreal to spend two years studying at the Art Students League of New York. She returned to Montreal in 1948 where she met her husband, artist Joe Prezament; they were married within five months.

They had two daughters. Joe died in 1983 at the age of 60, and Briansky never remarried after his death. “He was far more experimental than I was,” she says of her late husband’s art. “He was figurative, leaning toward the abstract, and was just finding his artistic voice when he took ill and died.”

She has been featured in a documentary called The Wonder and Amazement (“I want to call it The Agony and the Ecstasy,” Briansky quips.), a full-length feature about her, made by Dov Okouneff and Janet Best.

Rita Briansky is modest to a fault. More interested in the success of the many generations of students she has taught, she seems to have no idea of how brilliant and bold her own career has been. It has embraced various media, including print-making, watercolours, pastels, and oils, and through it all, she has taught continually – first at Westmount’s Visual Arts Centre from the early 1970s until 1983, when she moved to the former Saidye Bronfman Centre School of Fine Arts. Toward the end of her time at the Saidye Bronfman Centre, about a year before it closed in 2007, she began teaching at the Golden Age Club (now the Cummings Jewish Centre for Seniors), where she has been teaching a sold-out class ever since.

“By teaching, I’m learning. And I’m proving that ageing doesn’t mean that you stop growing. I’m not talking about me now; I’m talking about us. As I get older, I realize how important it is to keep working and keep my mind working. In teaching, I do a lot of research. I present my students with a theme for each semester. The theme for this winter has been painting interiors,” she says.

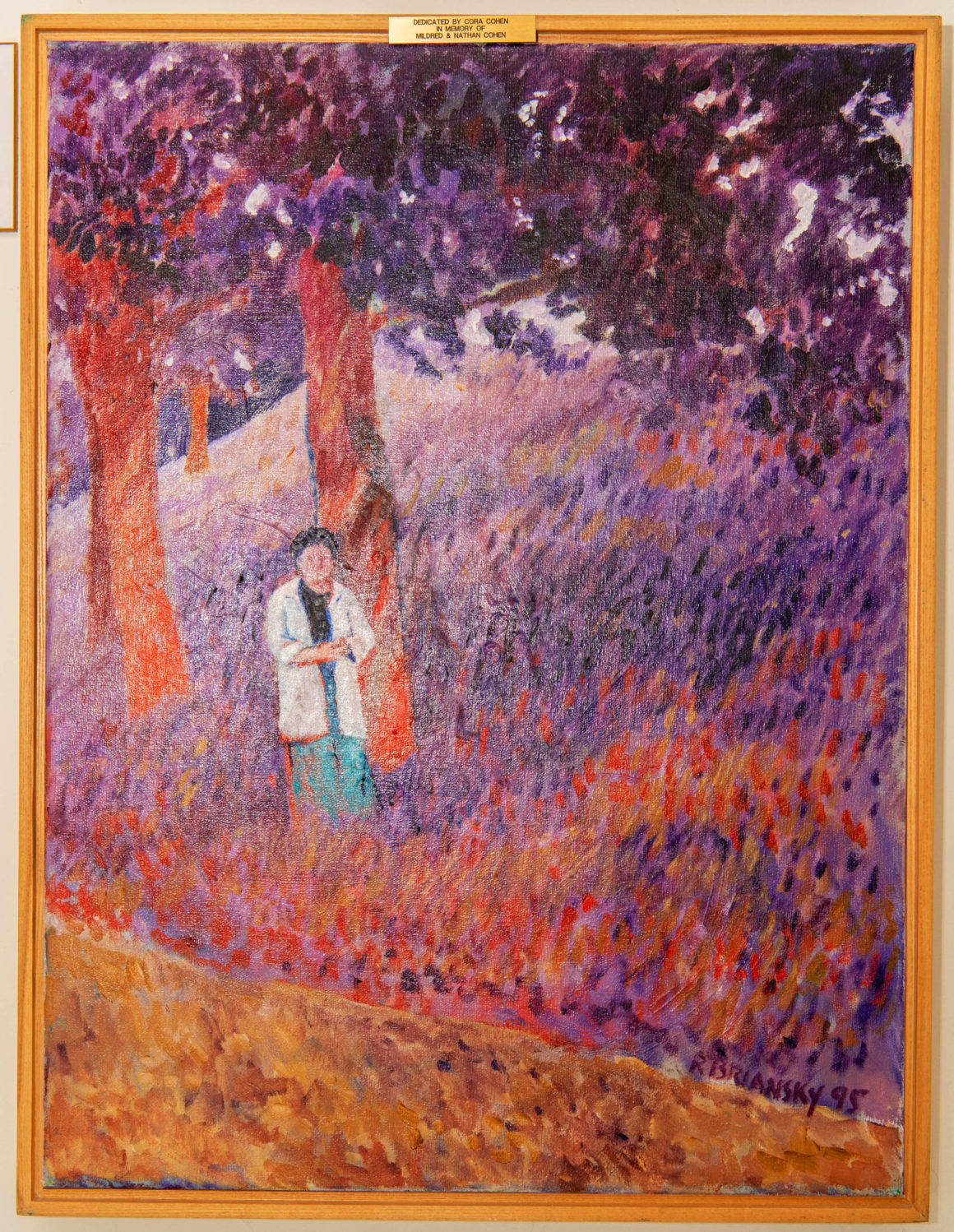

In 1995, Briansky went back to her roots in Poland, where she visited her hometown. There, she found the former Jewish cemetery, now transformed into an apartment building. Where the Jewish ghetto had once stood, there was a travelling circus. Where her family home had been, there was now a fish store; the same cobblestones and outdoor toilets were in the back.

She took photographs of everything, and after returning home, she created 18 paintings. The very important “Kaddish Series (Jewish Prayer for the Dead)” is on permanent display at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal. “I did not go with the intent of making paintings. But I felt I had to record what I felt. And since I had not experienced the violence – I only experienced the sorrow and the loss – this is what I painted.”

Upon returning to Montreal from that trip, Briansky was in a state of mourning. During her visit to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps, she had asked the guide what had been done with the ashes of the dead. “And he said: ‘At first they threw them into the river, but they blocked the river. So they put them into the ground.”

It was a time of year when poppies were growing profusely in the fields. And she realized that the beautiful landscape was fertilized by human ashes.

There are a few paintings of amazing fields of poppies and riotous colours; the visual beauty belies the grief; it is a fabulous juxtaposition of emotions.

“Artists are often known for a certain theme,” she says, “but I have many themes because I’m interested in many things.”

It is the beautiful sense of self-sufficiency and optimism that have reigned side by side in Rita Briansky throughout her life and career that we see reflected in her art. These have sustained her throughout her difficult beginnings and they are revealed in her varied and diverse work. Colour, negative space, not limiting programs and subject matter; they’re all there.

Briansky seems to have no sense of how talented and brilliant she is. Her naïve and energetic charisma is wholly delightful and engrossing.

One truly knows – not thinks – that, if in trouble, one could ring her doorbell and be offered a cup of tea, a tarot reading, and maybe even get a portrait done along with some very wise words of wisdom. What more could one ask of a great artist? •

Originally published in the Spring 2020 issue.