PHOTOGRAPHY: JOYELLE WEST

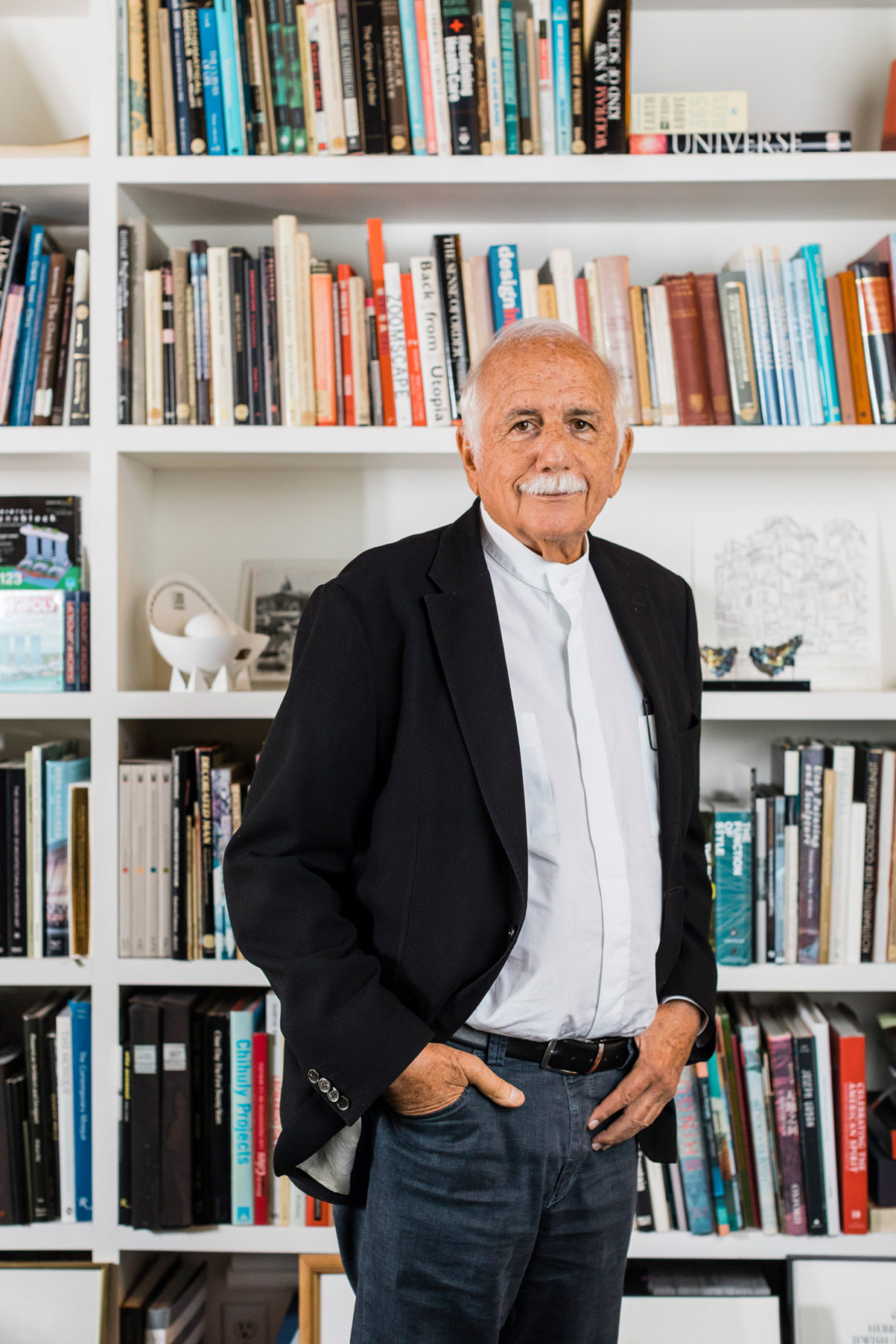

With a holistic vision for architecture that began before he achieved world fame as the young man who created Habitat ’67, Moshe Safdie – in his white shirt and black blazer – shines as brilliantly as the colours of the bright fall day on which we meet in his Boston offices.

Thank goodness! Is it because, at 81, Safdie is as busy and optimistic as ever? Is it because the world has finally caught up with his futuristic and ergonomic thinking that, 52 years ago, was so incredibly ahead of its time?

Safdie has left his mark on the earth, figuratively, literally, and philosophically – worldwide, and on every continent.

He was born in Haifa, Israel in 1938 to parents who created a successful garment business once they arrived in Canada in the early 1950s. They gave him a hard time about studying architecture at McGill University, and he had to divide his student days between his studies and working for the family business.

“But I tend to think now more in terms of ‘form follows purpose.’”

Moshe safdie

He came to world attention as the wunderkind who was awarded, at age 26, the contract to design Habitat ’67, the major theme exhibition of the 1967 Montreal World Exposition. Habitat pioneered a vision for urban housing using the technology of pre-fabricated construction, and a design that incorporated dwellings, gardens and commercial spaces.

His legacy includes airports, museums, libraries, government buildings, and entire communities of housing and mixed-use structures. He likes to say that his practice has resisted specialization (except for his penchant for saving the world with Habitat-like urban designs, which we will get to later). “After we did Vancouver Library, we were stereotyped as specialists, which meant we went on to do Salt Lake City Library and now Boise Library, but generally, I prefer to work on many building types. One project I would like to do still … is a stadium,” he says.

As we sit down, Safdie, an excellent teacher from his days at Harvard University, explains how post-Modernist architecture became, as he describes it, “precious” design. I remark: “I have never heard that term used before.” He quips: “That’s because I haven’t used it!”

He continues, saying that styling was “a noble and elegant side of architecture that followed the Modernist movement of the Second World War.”

“Some of us didn’t give up,” he says, “I consider myself part of that group who did not embrace Post Modernism and did not go for this kind of sculptural formalism. And what’s interesting is that one separates objectives and ethics from results. This doesn’t mean that the ethical framework was wrong. But I tend to think now more in terms of ‘form follows purpose.’ Is the interaction of the space fabulous for its intended purposes? This philosophy can apply to all spaces and all intended functions. It’s making an architecture that uplifts people’s spirits and at the same time, fulfills their basic needs.”

Safdie insists that it’s important to deal with the full spectrum of sustainability, of comfort, and of resources, while at the same time having the “sublime objective” of meeting both needs and beauty.

When the Home in Canada team recently visited Habitat ’67 (because the original apartment that still belongs to Safdie was on view to the public), I noted that those cubes and gardens do not seem futuristic, but homey. The small touches of elegance that for 1967 were incredibly forward-thinking are now de rigueur in any new build. The touches of homeliness, such as space in front of each home for plants, and checks in walls for privacy, are incredibly well thought out. Safdie had many utopian ideas, such as deliberately excluding odd-numbered floors from all elevators to require residents to reach their homes by the stairs, and placing cars far from their owners’ apartments to ensure that community members encounter each other. These have unfortunately not become part of the next generation’s zeitgeist.

“Did I set out at Habitat to create a work of art? To me, that’s an absurd starting point!” Safdie says. “I set out to solve a housing issue. Most architects today think that they have licence to do whatever they feel like. I personally feel like architects should have much more exacting missions than that. When an architect embraces that (philosophy), it is doomed to failure because architecture is not sculpture and it is not art in the sense of ‘anything goes.’ ”

There were attempts at other Habitat-style concepts, and some larger ones. A Habitat project in Puerto Rico in 1968 was abandoned and now lies in ruins. The New City of Modi’in in Israel is a success. But in the 1970s, Safdie says, “there was a big recessive moment in which urban development was not the focus” and he did not have the opportunity to do many more projects like Habitat.

It seems that the world has finally come around to his way of thinking and seeing. Demand in countries with enormous populations, such as China and India, has created an understanding of the need for his brand of thinking. Now he has huge projects, such as Raffles City Chongqing and Habitat Qinghuangdao.

These complexes have tree-lined streets many storeys up as well as on the ground, and high-end to low-end commercial centres within them. Depending on the size of the urban areas, there are libraries, swimming pools and parks – all of the elements that Safdie had initially envisioned for Habitat ’67 that were never built. He has designed, finally, his dream cities of the future. In my opinion he was always more of an idealistic urban planner, and architecture was his craft to that end. Now the world’s needs are catching up with his vision, enabling it to be more fully expressed.

During our interview, we discussed one of my favourite of his projects, which I had the pleasure of visiting last year: The Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resort. There, I met with one of his team of architects and I swam in the famous 146-metre-long rooftop pool. This is the amazing public space that put Singapore on people’s radar.

Completed in 2011, the Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resort was a competition launched by the government of Singapore. Safdie won the competition through an ingenious response to the limited land available, which caused him to place the hotel’s pool and park atop the sail-like hotel structure. He created windows to the sky instead of a wall of buildings, including a gorgeous lotus-like-shaped museum that allows light in through the tops of its soft petals, and a show-stopping glamorous retail promenade on the water from which fireworks are seen every night over the bay. He changed the city’s image, created a tourist destination. The city adores him.

The first time Safdie conceived of an indoor waterfall was for Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, completed in 2004. “For one thing, it shows you how architects evolve ideas from project to project,” he says. “They learn from them. In Ben Gurion, there was the idea to have a rotunda and I thought, how banal! So I thought, what if I did a dish and I suspended that dish column free over a gathering place from which you go to your plane? And then, of course, once you do a dish, it collects water at the bottom. And what are you going to do with it? So, I said: ‘let’s make a waterfall.’ And they all thought I was crazy. But we addressed the technical issues. In fact, this was the first waterfall in a public space in Israel and, as you know, water is very precious in Israel, and it was very meaningful.”

His second waterfall, a public art installation called the “Rain Oculus,” is a large dynamic whirlpool created in collaboration with artist Ned Kahn. As part of the Art Path at Marina Bay Sands, it was designed to engage people along the promenade, and acts as both skylight and rain collector, showering water into the enclosed retail space below.

And then, he did it again! He has now designed, for the third time, a fabulous waterfall in a building. This time, it’s in Singapore’s airport, and is called Jewel Changi Airport. In 2014, Safdie won the international competition to design the airport’s transportation hub. Under construction for five years, Jewel Changi Airport, which opened in the spring of 2019, is linked to three passenger terminals. The indoor waterfall – called the Rain Vortex – is the centrepiece that is surrounded by a forest. Jewel also has gardens, a hotel, and more than 300 retail outlets and dining facilities.

“When an architect does his job well, in a profound sense, what comes out you can call art.”

Moshe safdie

“It has a massive positive impact on air conditioning, on climate control; the garden is absolutely lush. Hundreds of thousands of people a day are coming into that building. It’s just caught the public imagination in a way that I’ve never experienced, not even with Habitat. It’s very satisfying,” Safdie says of Jewel.

Take a naturally occurring rain, or condensation, in a place where the weather creates this phenomenon, and use it to the advantage of the architecture to create a unique architectural feature. That is Safdie, bestowing his vision upon the world.

“When I design a major commercial centre for the airport, I end up making it one of the most famous gardens in the world, which doesn’t take away from the fact that it’s a great marketplace,” he says. Side by side, there’s nature and the bazaar.

“I think if you set out to create art, it’s going to be a fiasco. Architecture is a physical environment. If the architect does it well, materials come together: the space, the light, everything that constitutes architecture. The word art is very complicated for me because it is subject to a lot of interpretation. When an architect does his job well, in a profound sense, what comes out you can call art.”

As our interview draws to a close, Safdie looks at me and says: “I used to think: Why can’t Mozart just sit down and write a string quartet? But no, he had to have it commissioned by this or that. And I think architecture is that way too. If I was to design my own project, I would probably go back to the original Habitat. We only built a small piece of it; the mixed use was never realized. In some ways, I’ve addressed that in Chongqing and other projects, but to do it in a more holistic way, a village? That would be great for a finale.”

I muse: “If I dare say, what you’re saying is: Let’s create a better world, basically what you have been trying to design since Habitat?” And Safdie, an optimist, just like all the great designers, creators, dreamers and visionaries that I have had the honour and privilege to meet in this amazing series, says to me: “Well. I guess that is part of it. There are days when I am distressed, but I never give up because I am an optimist. I walk though some cities and I say ‘Why? Why this ugliness? Why this congestion? Why this irrationality?’ The challenge is not just to architects but to planners and our leaders.”

I hope that with the great visions and plans already shown to us by Moshe Safdie in so many beautiful spaces and places, we can all at least imagine what the world can be like in the future. •

https://www.safdiearchitects.com/media