The 19th century was a “banner year” for devastating fires in North America.

As legendary New York archivist Otto L. Bettmann wrote in The Good Old Days – They Were Terrible: “Between 1870 and 1906 four American cities – Chicago, Boston, Baltimore and San Francisco – burned to the ground, a record unmatched anywhere else in the world.”

William James / Public domain

Toronto and Montreal also experienced major conflagrations followed by a frenzy to rebuild. Toronto faced its first major fire on April 7, 1849. The Great Fire of Toronto began behind Graham’s Tavern on King Street and quickly spread to surrounding buildings. It consumed a wide area, including much of the Market Block, as the city’s business hub was known. It also damaged St. Lawrence Market south of King Street so severely, it had to be torn down. It is sometimes called the Cathedral Fire because it razed the prior incarnation of what is now St. James Cathedral.

Most of the buildings that burned down were constructed of wood. As in London, England two centuries before, building codes were drafted after fires to prevent future blazes. But in 1904, the Second Great Fire of Toronto would cause even more damage.

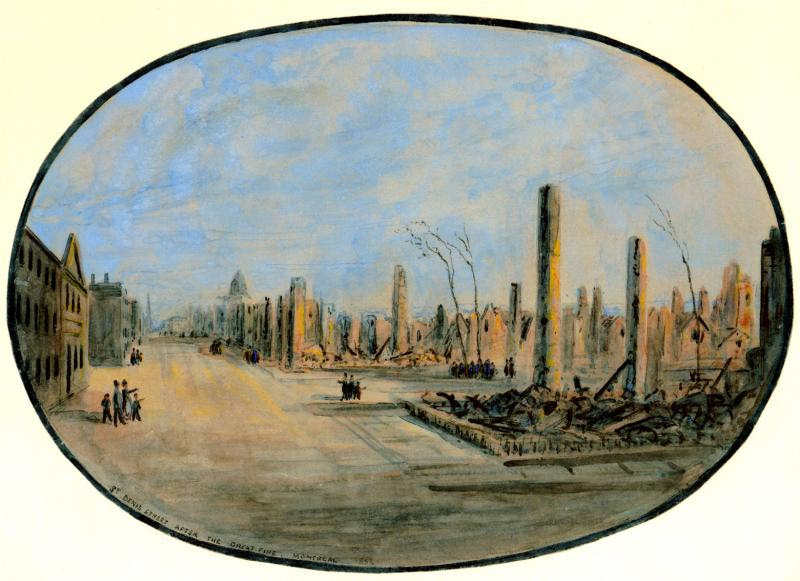

Around the same time in Montreal, the Great Fire of 1852 proved more devastating. Like the Toronto fire, it began in a tavern, this time on St. Lawrence Blvd. in the area now known as the Latin Quarter. But before it was over, one-quarter of the city would be destroyed, and close to one-fifth of its population homeless.

A reservoir located where today St. Louis Square stands had been drained. Without the water available, the fire spread quickly. It was fueled by wooden structures, many hastily built to house the influx of new immigrants and other workers during an industrial boom. But the fire did not spare the mansions of the elite, either.

Wood construction for homes and public structures was banned after the Great Fire of 1852. But many other approaches to building changed in the post-fire era. So much so, it was the beginning of the end of French influence on Montreal’s architecture.

Photo by Alexander Boon on Unsplash

Historian Paul-André Linteau notes in his book Brève histoire de Montréal (Montreal: Boréal, 1992) that the traditional French-style wooden house with gabled roof began to be replaced by those constructed of brick and with flat roofs. “A new type of row house, with a laneway running behind the lots, made its appearance in fashionable neighbourhoods: this was the British-inspired terrace house,” he writes.

The period also gave rise to the duplex and eventually the triplex. Larger, taller commercial buildings also began appearing, Linteau says, “…especially in Old Montreal, where new warehouses and office buildings were put up – resulting, however, in the elimination of a large part of the city’s French architectural heritage.” •