Photography: Larry Arnal

Clumps of patchy snow still clung to the ground on a frigid March evening when pandemonium erupted outside a Sault Ste. Marie pub. Paul VanderGriendt, a young flight instructor, was out with friends when a drunk teenager staggered out of the bar and attempted to drive away. As the men struggled to stop him, the teen rammed his truck into the crowd, crushing Paul underneath. He suffered a broken neck, ribs and shoulder blades, and a dislodged windpipe.

Airlifted to St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Paul was in intensive care for 101 days, kept in a drug-induced coma for several weeks to keep him immobile after delicate surgery. Doctors were amazed that he survived. Five months later, he was transferred to Lyndhurst Centre, a rehabilitation facility for adults with brain and spinal cord injuries. It is here that he learned from a former resident of a Toronto condo that had a unique arrangement for people with disabilities that a suite—a rarity—retro-fitted for wheelchair use, had just become available.

Accessible housing is a challenge for people with disabilities as the traditional model has been one of institutional or group home living. Amid the forests of shiny new condos that have been springing up in Canadian cities for the past two decades, accessibility has been a rare feature. But one building in Toronto’s Distillery Historic District broke that mold.

The unique set-up was the creation of the late Gary Sandler, a builder who had rapidly progressing multiple sclerosis that had paralyzed him. He wanted a place that would be accessible where he’d have attendant care that he could control. Private 24-hour care costing as much as $90,000 a year is not a possibility for most.

In 1997, Options for Homes, a non-profit developer, was just beginning to create a condo where owners would have input into developing their own building. Sandler jumped at the opportunity. He joined the board of directors and worked to ensure complete accessibility in the building’s design and to line up other buyers with disabilities who would pool a portion of their provincially appointed funding to hire on-site attendant assistance, enabling them to manage their own care.

After a series of challenging setbacks that left many buyers stranded, all the pieces finally fell into place. Today, the March of Dimes supplies the on-site caregivers who are on call for small day-to-day needs, giving users control over their lives without being tied to an institutional schedule.

“I use them two to four times a day,” says Greg Papp, an architectural technologist who often works from home and was one of the first buyers to employ the service. He suffered a spinal cord injury in a bicycle accident 27 years ago. “It could be anything—help with lunch, getting tea in the afternoon, adjusting the heat,” Greg says. “Many times in the past [living in co-op housing], I’ve been thirsty and stuck, or sitting, roasting in my jacket or needing the washroom . . . it’s still hard to talk about. There are some things that are very awkward to ask a neighbour to help you with. It takes all your courage. Here the staff are trained so there’s no worry and no guilt when you ask for help.”

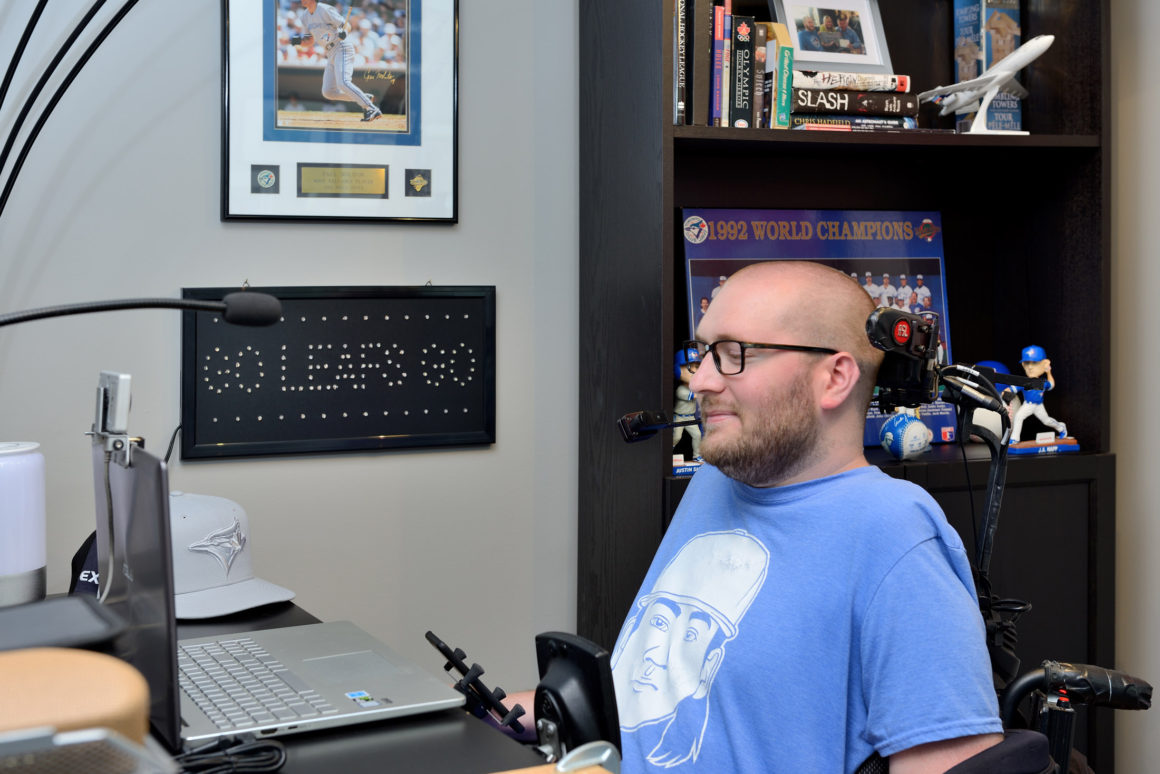

“Living here gives me the freedom I need to live independently,” adds Paul, who moved in January 2018. “The service is fantastic. There is very little turnover so that’s another plus. Without the on-site help I would not be able to hire someone to come for only 20 minutes at a time to assist me with lunch or get me ready for bed.” His family lives close by and provides pre-cooked meals for him.

The flexibility and reliability are life-changing he says, adding: “Knowing that someone will be there, and knowing who is coming through the door, gives me tremendous peace of mind.”

Another first is about to launch in Pickering, a city of 94,000 in Durham Region, east of Toronto. Axess Condos, the world’s first fully accessible condo project according to its developer Dan Hughes, is slated to see shovels in the ground later this winter.

Hughes is executive director of the Enhanced Day Program, which provides life skills for young adults with cognitive disabilities due to brain injury or such congenital conditions as Down syndrome and autism. His parents both have disabilities, and he has worked with youth and adults with special needs for more than two decades. He’s also a member of the City of Pickering’s accessibility committee.

Photo courtesy of Quadrangle and Human Space

“When I reviewed plans for other projects, I saw that many were not accessible,” he says. “So I founded my own development company, Liberty Hamlets, to provide fully accessible units that would also be inclusive for everyone—from people aging in place to people with physical disabilities or cognitive and mental challenges who, in the past, were not integrated into society. We often take the humanity out of how we build.

“Axess condos will allow families to stay together,” Hughes adds. “In Ontario, we have 1,700 families with both parents over 70 taking care of an adult child with disabilities and no plan for them.”

Photo courtesy of Quadrangle and Human Space

This includes families such as the Bashaws, retired seniors caring for their adult daughter who has autism, and looking to downsize. Hughes’s life skills program will be located on the ground floor, affording them respite care as well as some independence for their daughter who will be able to continue living in the suite after her parents pass on.

Features of the 320 units will include wider-than-standard corridors and doorways, walk-in showers, and rooms that afford a full turning radius for wheelchairs and scooters.

With a master’s degree in hospital design from Cornell University followed by studies in architecture and three years of research, Hughes is well versed in details that support accessibility, such as light and dark walls as well as acoustic contrasts (tile and carpet) in hallways that help the visually- and hearing-impaired orient themselves, demarcating where a wall ends and a door begins.

Photo courtesy of Quadrangle and Human Space

“We found that the costs of Universal Design are just one per cent above average if the adaptations are built in from the start,” Hughes says. “Instead of regular doorknobs, for instance, we will install levered doorknobs; instead of a tub in the second washroom, we install extra tiling for the roll-in shower stall. It’s a matter of the design choices we make. We are changing the future of housing.” •

Originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue.

Axess Condos Pickering

www.axesscondopickering.ca