Photography: James Law

Using the most innovative building materials as his paint brushes, and unusual cladding as his brush strokes, Frank Gehry is changing the building landscapes of our world. He is redefining the way we conceive of buildings and the way that we interact with them, as well as the way they impact the world around us. And as he does that, he is changing the way that we see all those spaces: How will we feel about the relationship between architecture and exterior spaces tomorrow?

What a marvellous liberation! It’s not just because his buildings defy gravity that one leaves an interview with this globally renowned architect feeling that the world is tilting!

is home to the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

Photo courtesy of Falkenpost

When I saw Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles – the home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra – for the first time, I felt as if I was seeing music! I wanted to dance! It made me so happy! The forms of the building, in steel and wood, seemed to leap and soar into the sky in a way I had never seen before. If the effect, as Gehry has said he wants to create, is to: “Transfer feelings through bricks and mortar,” then he has eminently prevailed. Both the building and the garden behind (reminiscent of Park Güell, Gaudi’s curvaceous Barcelona gardens), succeed in creating a haven for music and peace in the middle of a bustling city, where people can go to hear and feel what those spaces were created for.

Frank Gehry was born in Toronto in 1929 to a New York-born father and a mother who had immigrated from Poland. After the family migrated to California in 1947, Gehry enrolled in Los Angeles City College. After he thought about studying chemical engineering, he settled instead on architecture and graduated from the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California in 1954.

Photo courtesy of ChatridelSevilla

He is internationally known for designing striking and original structures: 8 Spruce Street, a 76-storey apartment tower in New York; the Louis Vuitton Foundation building in Paris; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain; the Pop Culture Museum in Seattle; the Peter B. Lewis building in Cleveland; the Dancing House in Prague, and the Art Gallery of Ontario, among many other iconic structures.

Photo courtesy of Dronimages

His was not the quickest rise to fame to become one of the world’s most renowned architects of Canadian origin. But the transformation of his own home – a Dutch colonial style house in Santa Monica, starting in 1978, was the beginning of his own transformation as well. He took his land and house, and with the use of chicken-coop wire and corrugated metal and other metals, sure to anger the neighbours, tore down the exterior of the original structure, and extended it with these “modern artifacts.” Depending on point of view, he thus created what is either an abstract study worthy of artist Andy Warhol or a travesty, which has been attracting tour buses for decades. He laughs about the winds of fame telling him how popular he is by how many buses pass the house daily.

But it was his design of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, which was so revolutionary, so gorgeous, and came in under cost and on time, (and, as he laughs, “with no leaks”) that changed the city’s very makeup. It caused peace. It caused financial prosperity. It attracted hordes of tourists and put the city on the map. It caused what is now called the “Bilbao effect.”

Photo: James Law

Perhaps this is why his name has become synonymous with great abstract architecture, and he is referred to as the Frank Lloyd Wright of his generation.

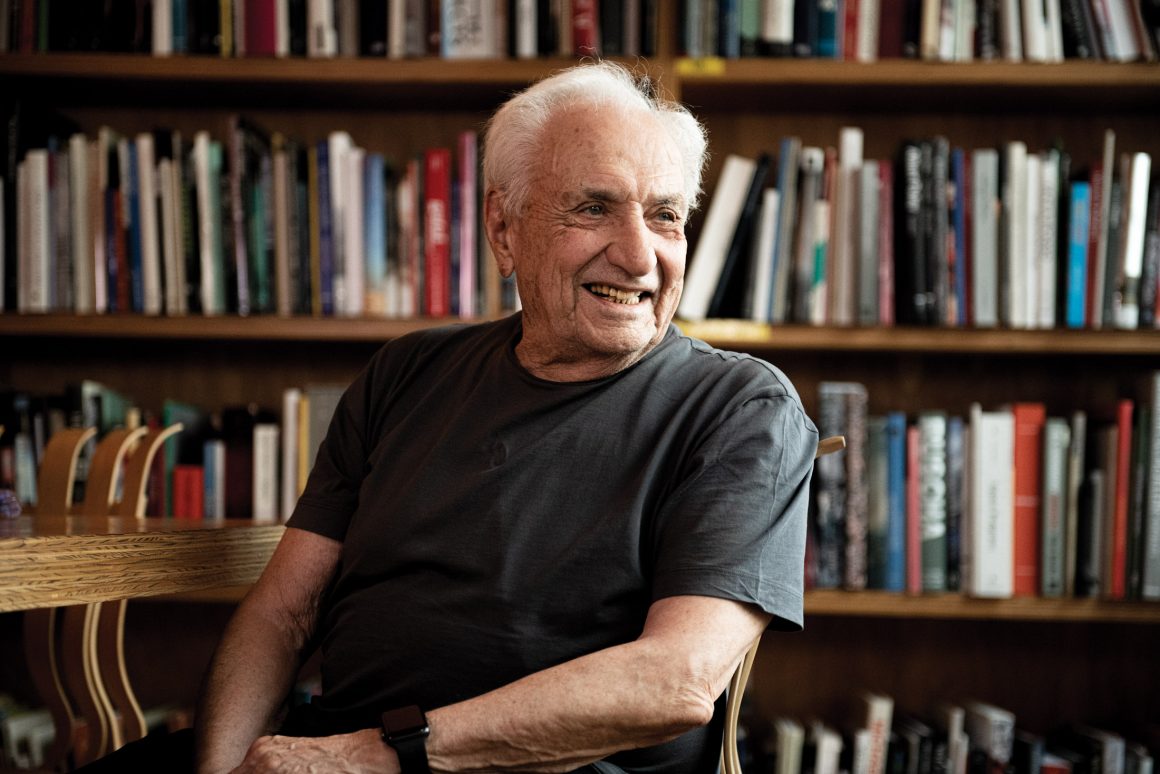

Our meeting took place in a brief visit to Gehry’s huge loft-like studio in Los Angeles. We were permitted to take photos only in two small libraries. But as I wandered around, I marvelled at the huge scope and breadth of the work Gehry is doing and has done: whole cities and huge projects around the globe.

“I believe architecture can rise to the level of fine art within the constraints of the construction industry,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Till Niermann

In 2002, he partnered with Dassault Systèmes, a subsidiary of the French aircraft-design company Dassault Group, to bring 3D computer-aided design to his architecture. The software was originally developed for the aerospace industry and it was the first time an architecture firm had used this technology. Because of advanced quoting and structural engineering capabilities, Gehry’s projects come in under cost every time and are able to be built to exact specifications. This is remarkable in his industry, and especially important for building the complex and visually remarkable structures that he designs.

on the Rašín Embankment in Prague, Czech Republic. Designed by the Croatian-Czech architect Vlado Milunic in cooperation with Frank Gehry on a vacant riverfront plot, it was completed in 1996.

Photo courtesy of Iva Balk

A huge Canadian flag hangs upon a wall as one faces the stairs that come down from his library and private office, and I must have stood for 15 minutes before a magnificent model of his upcoming project in Arles, which made me truly understand how Gehry is an abstract artist in the most three-dimensional art of all: architecture. The Luma Arles complex, an arts centre in France, is breathtaking with its breadth, scope and artistry.

Layers of aluminum tiles clad the building, so that each one resembles a brush stroke. The effect is stunning, ever-changing. Each tile catches the sun at a different angle. Then, as the sun makes its inevitable turn around the building, the structure catches the light and glows, literally! And changes colour. No two minutes of the day are the same. The building itself IS a work of art, but not a static, two-dimensional one; instead, it’s a three-dimensional, living, breathing, almost-moving one, in which people work. It resembles a painting by Vincent Van Gogh.

Image courtesy of the AGO

It is a marvel of modern technology that has been created by a brilliant, artistic talent. This marriage of art and technology is really what Frank Gehry is all about. It seems as if he is to physically standing structures, (that are meant to be lived in) what Van Gogh was to paint and the use of a palette knife. I propose that this places Gehry in a league of his own and ups his own game, even higher than that which we saw from the “Bilbao effect.”

“I tried to have that happen naturally,” he says. “I tried to have the building materials become the watercolour, the frame. It’s about what surfaces look like…their colours.”

Photo by iwan

“I thought we should try to create our own language for our own time,” he adds. “How do you do that? Our own time is moving, everything is moving. Planes, cars, everything. So, I was looking for a way to express that with thinner materials, and then I saw the picture of the charioteer from 500 B.C. And it was so moving, it made me cry. And I wanted to create architecture that would move people like that piece of art moved me.”

Photo courtesy of Manolo Franco

The ancient Greek charioteer paradoxically influenced Gehry to become the most modern of architects. This and other archeological wonders inspired him to draw and create fish forms, such as the fish sculpture in Barcelona for which he used the advanced 3D technology of Dassault. It allowed him to create his buildings “on time, under budget and without leaks.” He is very proud, as well he should be of those facts. Gehry is a true Renaissance artist, designing sets for opera, a sailboat, another house, as well as his many apartment buildings and museums. He says he would love to try a synagogue or other house of worship.

In giving back to his community, Gehry is involved in an organization called Turnaround Arts: California, which works with 27 elementary schools to encourage children through art to engage in school. The program fosters art education by mentoring principals and teachers and by giving students such creative resources as arts supplies, musical instruments, and licensing rights to perform school musicals.

establishment dedicated to contemporary popular culture in Seattle, Washington. It opened in 2000, and has been compared to electric guitar equipment used by such artists as Jimi Hendrix.

Once again, as I do with all these interviews, I ask him if feels Canadian (he owns a large collection of hockey sweaters that line the upper walls of his office). And he says yes, after all these years of living in the United States, somehow he still feels both protective of and protected by and for his native Canada. I like the sentiment so much, that I don’t push him for what he means. The most important thing, as I continue this series on these extraordinary Canadians, is that I get a sense for us, on how they think, what makes them so fascinating.

And once again, at 90, this amazing man says that he has no intention of slowing down. That he adores what he does, so why would he? I say: “You are an artist using new materials to create emotion out of form, exactly as you said you wanted to do when you started out!”

He says: “Yes, I like that. I believe in the art of architecture.”

establishment dedicated to contemporary popular culture in Seattle, Washington. It opened in 2000, and has been compared to electric guitar equipment used by such artists as Jimi Hendrix.

I say: “But you’ve pushed the boundaries.” He replies: “Well. you know, Bernini did it. He had a construction industry. He had the popes, he had clients. There were fights over who did what; there was jealousy between the various architects of his time. You know, it’s not changed; but they made great buildings.”

In every generation, and in every time, there will be constraints, but there will always be one or two who rise above them and whose work will be examples for generations to come. I believe that among those is Frank Gehry who has pushed the envelope to reveal the future, which is now, which is here, which is, evidently, quite beautiful, in an unpredictable way. I am so excited to see what he will do next! What a great honour it was to meet this remarkable Canadian architect. •

Originally published in the Autumn 2019 issue.